“The Knot!” barks the instructor. “If you leave here knowing nothing else, remember that! It will save your life.”

We all stop smiling and study the double Figure Eight tied through the belay loops of our harnesses. Strange how thin a 10.2 millimetre nylon rope looks when you have to hang from it. Guess this is why climbing is called serious fun.

But this is not about having fun. It is about work… really. A series of assignments require me to visit South America , specifically Huaraz , Peru , a veritable Mecca for serious hikers and climbers.

OK, so maybe it is not all work, and turning 40 may come into play – a bit. Truth is, straddling Baby Boomer and Generation X age groups, I secretly nurse a passion to feel the oxygen-deprived exhilaration of climbing a geo-giant like Peru ’s Huascaran Mountain at 6,807 meters (22,334 feet) above sea level. One obstacle remains: I have to become a serious hiker and climber – fast!

To get from novice to expert in a mere month I drop into the Crux Climbing Centre, an indoor climbing gym in Kelowna , British Columbia , south of my home. Owner Greg McHatton says taking a crash course in rock climbing is an oxymoron. Rather than get insulted, I sign up. That’s when reality hits.

During my first session I realize that my nimble days as a spider monkey are long gone. Regaining the hand strength, technique, endurance and (good grief) weight loss needed to scale rock walls means real work.

*****

The runway lights of Lima ’s Jorge Chávez International Airport (LIM) sparkle through the cold night smog. Things look pretty flat.

I grab my gear and jump into a torrent of people flooding the arrivals gate. After 23 hours of travel, with stops in Calgary and Houston , I do not care if I sleep on a bed, a cot or a straw tick, so long as it is horizontal.

As it turns out, my host, Randy Easthouse, a linguistic specialist with Wycliffe Canada , has made arrangements for me at a private guesthouse in Miraflores, Lima ’s ritzy tourist district.

After a decent sleep, a Spartan breakfast of fried bread, processed cheese and a gringo version of Americano-style coffee, I am ready to roll.

Randy theft-proofs our gear under a tarp and fires up the diesel pickup. “If you can drive in Lima , you can drive anywhere,” he says gunning the engine. “Buckle up.”

An hour’s drive north on the Pan-Pacific Highway the real estate takes a serious turn for the worse.

The contrast between modern Lima and its outskirts is mind-boggling. Away from the urban area, people smile and wave at us from sprawling shantytowns of packed earth walls and tin roofs. Peru has a population the size of Canada stuffed into a country the size of Quebec with a Gross Domestic Product more than a third that of Ontario .

Two hours later, we turn at Barranca to the coastal fishing community of Chorrillos and pull up to a whitewashed adobe restaurant called Sombrilla, or “bit of shade”.

Seated under a canary yellow awning on the patio, we savour sudado lenguado, a dish of steamed flounder smothered in sweet onions, cilantro, ginger and picante sauce. Local surfers entertain on the beach as we ponder the artistic conundrum across the bay: a 40-meter tall statue of Jesus atop a hillside mosaic of painted rocks advertising Cristal, a popular national beer.

We don’t stop long.

On the floodplains of Paramonga, we leave the shoreline and head west into a wide valley framed by razorback ridges extending like ribs from the Andean spine that runs the length of the continent. The road cuts a swath through irrigated sugarcane plantations, turning abruptly in crazy right-angle corners without warning.

It is in one of these corners that I have an epiphany: A bus, careening toward us on two wheels, barely misses us and leaves in its wake the grim realization that there is often more danger in the journey than the actual destination.

We leave the cane-carpeted valley floor and climb upward through a three-hour series of stacked switchbacks.

It is dark by the time we arrive in Huaraz at another private guesthouse. Most of the town’s 66,000 inhabitants are asleep. Most of their dogs and roosters are not.

Dawn is spectacular. Filling the horizon, loooming three kilometres straight up and god-like over the town is the mountain, Huascaran , both majestic and foreboding.

I check my climbing gear and practise “The Knot”, anxious to get underway. I soon learn a critical lesson the hard way: It takes days, not hours to acclimatize – and high altitude sickness is nothing to triffle with. What is supposed to be a breathtaking excursion above Lake Llanganuco becomes a miniature midlife crisis.

At 4,300 meters (14,000 feet) and well into our trek, I am hit with what can only be described as the worst hangover of my life. With every step, my pulse pounds behind aching temples at 170 beats per minute. I am panting for air, dejected.

Before the climb, I drank the Peruvian cure – matte de coca (cocoa leaf tea) – and spiked my water with aerobic oxygen drops to combat the thin air, but now the game plan needs reworking. It seems wiser to try later.

Days later, after visiting different villages, I learn the secret to acclimatization: “Climb high, sleep low.”

I am set to take another stab at my newfound sport, although a more subdued version of the original plan.

My guide, a proud Quechua Indian named Ade Yanac, introduces me to friends, Felix “Gato” Sanchez and Jon Jarvis. Together we drive to a rock face above the town of Monterey , one hour west of Huaraz.

These guys know what they were doing. By the time I slip into my harness and tighten my shoes, Gato has lead climbed a route rated 5.10c for difficulty and fed a rope down through a set of anchor chains some 30 metres overhead.

“Your turn,” says Ade, checking the rope I have tied to my harness.

“On belay,” I call.

“Belay on!” replies Ade as he takes up the slack.

“Climbing,” I announce. And trusting the knot, I jam my chalked fingers into a crack in the rock face and begin the ascent.

Halfway up the wall, with adrenaline pumping, the epiphany returns, revised. I realize there are often more joys on the journey than at the destination.

I am climbing a dream in Peru at 40 – and the view just keeps getting better.

Climb on.

By the way:

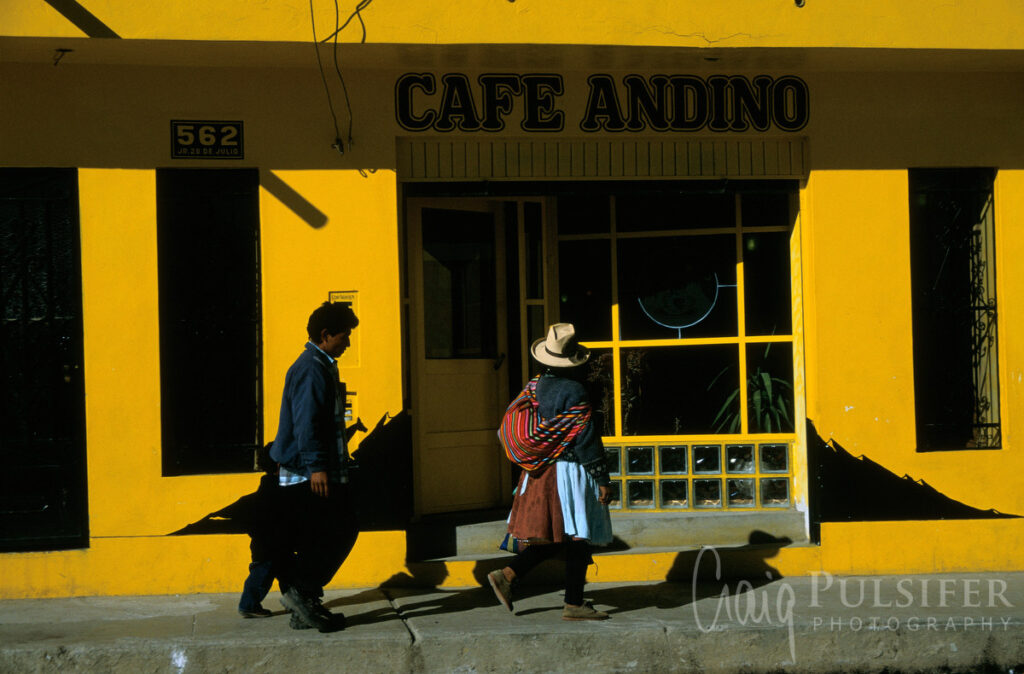

- On May 31, 1970, an earthquake mearuing 7.8 rocked central Peru killing 66,794 people. Although Huaraz was levelled, many of its citizens survived. At nearby Unguay, the quake triggered an avalanche and landslide from the Huascaran Mountain that buried the town. Thirty-two years later, the original Unguay is buy a memorial, while many areas of Huaraz still look cobbled together from bits and pieces of broken past. The downtown core, however, shows signs of prosperity: Corners are peppered with all manner of shops, street vendors and moneychangers. Fine international restaurants have sprung up, such as Café Andino with its rich library of trekking books and free over-the-counter advice, and Pizza BB, whose name belies its oven-baked bread and pastas made by its Parisian owner.

- High-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) and high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), which are subsets of Acute Mountain Sickness, can affect anyone travelling to high elevations. There is no evidence to suggest that one’s susceptibility is based on age, gender, physical fitness or previous altitude experience. While these illnesses are typically not experienced below 2,500 metres, goal-driven climbers who push for higher elevations frequently encounter the potentially life-threatening complications of climbing too high, too fast. The condition causes fluid retention in the lungs or brain characterized by extreme listlessness, inability to walk or sleep, coughing up blood or sputum and confusion to the point where one can think he or she is fine. The cure is as simple as descending. However, left untreated, the results can be fatal.